An eye specialist’s capacity to see the big picture continues to inspire others.

An eye specialist’s capacity to see the big picture continues to inspire others.

When South African-born Geoff Cohn left Sydney in 1981, he never expected to see Australia again. He had spent four years at the University of NSW training as an eye surgeon and was returning home with specialist skills.

Cohn’s inspiration to become an ophthamologist came from a one-year national service stint in a Kalahari Desert mission hospital. He realised that as a medical graduate he could handle just about anything but he had no idea about eyes. He also realised that a simple cataract operation could prevent or reverse blindness – but the world’s poorest people did not have access to basic eye health or funding.

Cohn, who was made a Member of the Order of Australia in January, put his new skills to good use, working for the next two years as the only eye surgeon for 2.5 million people in Bophuthatswana, an ethnic homeland in north-western South Africa.

“In the first year we saw 32,000 people and in the second year 43,000,” recalls Cohn, 58, who also trained local doctors and nurses in basic eye skills.

He resettled in Sydney in 1983 and set up a private ophthalmological practice, as well as lecturing at the University of NSW (he’s currently taken a leave of absence from the university to spend more time with his sons, aged 17 and 24).

If the story ended there, Cohn would be one of thousands of South Africans who have fled apartheid to create a better life in Australia. He’d have a very comfortable life as a Macquarie Street eye surgeon, perhaps doing a bit of pro bono work.

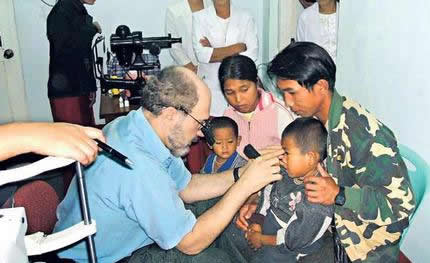

In reality, Cohn’s aid work – in Myanmar, Indonesia, PNG and Cambodia – is a second full-time job and his Sydney practice is a way to support himself and the tens of thousands of cataract operations he has performed, or organised other surgeons to perform, on people who would otherwise be blind.

He started in Indonesia in 1988, eventually helping to set up three surgical programs funded by Rotary and the John Fawcett Foundation. In 1993, he began training surgeons and support staff in PNG, then in 1998 he did the same in Cambodia.

For the past eight years, Cohn has focused on the See Again Myanmar project, where he has helped set up four centres in or near monasteries, as well as a permanent team of five local employees to teach other locals how to conduct ophthalmic screening.

“That means the surgeons can just turn up and operate, instead of examining burning, itchy eyes,” says Cohn, who estimates he has organised more than 100 Australian eye surgeons to visit Myanmar for two-week stints (as well as going 14 times himself)

Geoff Cohn at work.

An eye specialist’s capacity to see the big picture continues to inspire others.

When South African-born Geoff Cohn left Sydney in 1981, he never expected to see Australia again. He had spent four years at the University of NSW training as an eye surgeon and was returning home with specialist skills.

Cohn’s inspiration to become an ophthamologist came from a one-year national service stint in a Kalahari Desert mission hospital. He realised that as a medical graduate he could handle just about anything but he had no idea about eyes. He also realised that a simple cataract operation could prevent or reverse blindness – but the world’s poorest people did not have access to basic eye health or funding.

Cohn, who was made a Member of the Order of Australia in January, put his new skills to good use, working for the next two years as the only eye surgeon for 2.5 million people in Bophuthatswana, an ethnic homeland in north-western South Africa.

“In the first year we saw 32,000 people and in the second year 43,000,” recalls Cohn, 58, who also trained local doctors and nurses in basic eye skills.

He resettled in Sydney in 1983 and set up a private ophthalmological practice, as well as lecturing at the University of NSW (he’s currently taken a leave of absence from the university to spend more time with his sons, aged 17 and 24).

If the story ended there, Cohn would be one of thousands of South Africans who have fled apartheid to create a better life in Australia. He’d have a very comfortable life as a Macquarie Street eye surgeon, perhaps doing a bit of pro bono work.

In reality, Cohn’s aid work – in Myanmar, Indonesia, PNG and Cambodia – is a second full-time job and his Sydney practice is a way to support himself and the tens of thousands of cataract operations he has performed, or organised other surgeons to perform, on people who would otherwise be blind.

He started in Indonesia in 1988, eventually helping to set up three surgical programs funded by Rotary and the John Fawcett Foundation. In 1993, he began training surgeons and support staff in PNG, then in 1998 he did the same in Cambodia.

For the past eight years, Cohn has focused on the See Again Myanmar project, where he has helped set up four centres in or near monasteries, as well as a permanent team of five local employees to teach other locals how to conduct ophthalmic screening.

“That means the surgeons can just turn up and operate, instead of examining burning, itchy eyes,” says Cohn, who estimates he has organised more than 100 Australian eye surgeons to visit Myanmar for two-week stints (as well as going 14 times himself).

In Sydney, he spends much of his time organising donations of equipment, as well as fundraising for the $US30,000 ($32,760) a year it costs to run each Burmese centre – with a fair amount coming from his own pocket. “I couldn’t think of a better way to spend it,” he says. “Seeing a child who was blind yesterday walking around and picking up a toy, that’s quite something.”

THE BIG QUESTIONS

Biggest break It was only at 22, just before I graduated in medicine, that I realised the only way to be successful was to isolate a task into a manageable size and deal with it.

Biggest achievement Being able to inspire medical students and colleagues in many different countries to see their role in a wider context.

Biggest regret I have met lots of extraordinary people whose talents could reach far beyond their self-imposed limits. I would have loved to inspire them to reach beyond it to a more satisfying, less materialistic place.

Best investment Time and money spent on setting up eye programs in Africa, Indonesia, PNG, Cambodia and Myanmar. The multiplier effect is infinitely gratifying as our trainees spread the skills.

Worst investment Placing an eye clinic and operating theatre in Irian Jaya, overlooking the turmoil. The surgeon I trained could not commit ongoing attention to the cataracts because of other demands on his time, so that the skills rusted along with the equipment.

Attitude to money It provides the means to act – at least in our little microcosm. It can alleviate suffering and bring happiness. Money can also be a carapace, anchoring the spirit, if we allow it to own us.

Personal philosophy To create a better future [with aid work], incorporating care for those who need it here and abroad.